Build your own interactive JavaScript playground

Recently I spent some time working on my own JavaScript playground called Demoit. Something like CodeSandbox, JSBin or Codepen. I already blogged about why I did it but decided to write down some implementation details. Everything happens at runtime in the browser so it is pretty interesting project.

The goal

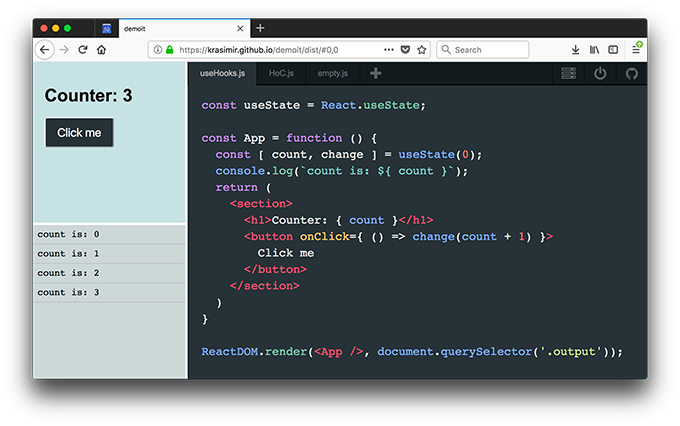

The JavaScript playground is a place where we can write JavaScript code and see the result of it. This means changes in a DOM tree or logs in the console. To accommodate those needs I created a pretty standard UI.

We have two panels on the left side - one for the produced markup and one for the console logs. On the right side is the editor. Every time when we make changes to the code and save it we want to see the left panels updated. The tool must also support multiple files so we have a navigation bar with tabs for every file.

The editor

Nope, I did not implement the editor by myself. That is a ton of work. What I used is CodeMirror. It is a pretty decent editor for the web. The integration is pretty straightforward. In fact the code that I wrote for that part is just 25 lines.

// editor.js

export const createEditor = function (settings, value, onSave, onChange) {

const container = el('.js-code-editor');

const editor = CodeMirror(container, {

value: value || '',

mode: 'jsx',

tabSize: 2,

lineNumbers: false,

autofocus: true,

foldGutter: false,

gutters: [],

styleSelectedText: true,

...settings.editor

});

const save = () => onSave(editor.getValue());

const change = () => onChange(editor.getValue());

editor.on('change', change);

editor.setOption("extraKeys", { 'Ctrl-S': save, 'Cmd-S': save });

CodeMirror.normalizeKeyMap();

container.addEventListener('click', () => editor.focus());

editor.focus();

return editor;

};

The constructor of CodeMirror accepts HTML element and a set of options. The rest is just listening for events, two keyboard shortcuts and focusing the editor.

In the very first commits I put a lot of logic in here. Like for example the transpilation or reading the initial value from the local storage but later decided to extract those bits out. It is now a function that creates the editor and sends out whatever we type.

Transpiling the code

I guess you will agree with me if I say that the majority of JavaScript that we write today requires transpilation. I decided to use Babel. Not because it is the most popular transpiler but because it offers a client-side standalone processing. This means that we can import babel.js on our page and we will be able to transpile code on the fly. For example:

// transpile.js

const babelOptions = {

presets: [ "react", ["es2015", { "modules": false }]]

}

export default function preprocess(str) {

const { code } = Babel.transform(str, babelOptions);

return code;

}

Using this code we can get the JavaScript from the editor and translate it to valid ES5 syntax that runs just fine in the browser. This is all good but what we have so far is just a string. We need to somehow convert that string to a working code.

Using JavaScript to run JavaScript generated by JavaScript

There is a Function constructor which accepts code in the format of a string. It is not very popular because we almost never use it. If we want to run a function we just call it. However, it is really useful if we generate code at runtime. Which is exactly the case now. Here is a short example:

const func = new Function('var a = 42; console.log(a);');

func(); // logs out 42

This is what I used to process the raw string. The code is send to the Function constructor and later executed:

// execute.js

import transpile from './transpile';

export default function executeCode(code) {

try {

(new Function(transpile(code)))();

} catch (error) {

console.error(error);

}

}

The try-catch block here is necessary because we want to keep the app running even if there is an error. And it is absolutely fine to get some errors because this is a tool that we use for trying stuff. Notice that the script above catches syntax errors as well as runtime errors.

Handling import statements

At some point I added the ability to edit multiple files and I realized that Demoit may act like a real code editor. Which sometimes means exporting logic into a file and importing it in another. However, to support such behavior we have to handle import and export statements. This (same as many other things) is not built-in part of Babel. There is a plugin that understands that syntax and transpile it to the good old require and exports calls - transform-es2015-modules-common. Here is an example:

import test from 'test';

export default function blah() {}

gets translated to:

Object.defineProperty(exports, "__esModule", {

value: true

});

exports.default = blah;

var _test = require('test');

var _test2 = _interopRequireDefault(_test);

function _interopRequireDefault(obj) {

return obj && obj.__esModule ? obj : { default: obj };

}

function blah() {}

There is no result of that yey but at least the code gets transpiled correctly with no errors. The plugin helps to have the correct code as a string but has nothing to do with running it. The produced code didn't work because there is no require neither exports defined.

Let's go back to our executeCode function and see what we have to change to make the importing/exporting possible. The good news are that everything happens in the browser so we do actually have the code of all the files in the editor. We know their content upfront. We are also controlling the code that gets executed because as we said it is just a string. Because of that we can dynamically add whatever we want. Including other functions or variables.

Let's change the signature of executeCode a little bit. Instead of code as a string we will accept an index of the currently edited file and an array of all the available files:

export default function executeCode(index, files) {

// magic goes here

}

Let's assume that we have the files of the editor in the following format:

const files = [

{

filename: "A.js",

content: "import B from 'B.js';\\nconsole.log(B);"

},

{

filename: "B.js",

content: "const answer = 42;\\nexport default answer;"

}

]

If everything is ok and we run A.js we are suppose to see 42 in the console. Now, let's start constructing a new string that will be sent to the Function constructor:

const transpiledFiles = files.map(({ filename, content }) => `

{

filename: "${ filename }",

func: function (require, exports) {

${ transpile(content) }

},

exports: {}

}

`);

transpiledFiles is a new array that contains strings. Those strings are actually object literals that will be used later. We wrap the code into a closure so we avoid collisions with the other files and we also define where require and exports are coming from. We also have an empty object that will store whatever the file exports. In the case of B.js that's the number 42.

The next steps are to implement the require function, and execute the code of the file at the correct index (remember how we pass the index of the currently edited file):

const code = `

const modules = [${ transpiledFiles.join(',') }];

const require = function(file) {

const module = modules.find(({ filename }) => filename === file);

if (!module) {

throw new Error('Demoit can not find "' + file + '" file.');

}

module.func(require, module.exports);

return module.exports;

};

modules[${ index }].func(require, modules[${ index }].exports);

`;

The modules array is something like a bundle containing all of our code. The require function is basically looking into that bundle to find the file that we need and runs its closure. Notice how we pass the same require function and the module.exports object. This same object gets returned at the end.

The last bit is executing the closure for the current file. The generated code for the example above is as follows:

const modules = [

{

filename: "A.js",

func: function (require, exports) {

'use strict';

var _B = require('B.js');

var _B2 = _interopRequireDefault(_B);

function _interopRequireDefault(obj) { return obj && obj.__esModule ? obj : { default: obj }; }

console.log(_B2.default);

},

exports: {}

},

{

filename: "B.js",

func: function (require, exports) {

"use strict";

Object.defineProperty(exports, "__esModule", { value: true });

var answer = 42;

exports.default = answer;

},

exports: {}

}

];

const require = function(file) {

const module = modules.find(({ filename }) => filename === file);

if (!module) {

throw new Error('Demoit can not find "' + file + '" file.');

}

module.func(require, module.exports);

return module.exports;

};

modules[0].func(require, modules[0].exports);

This code gets sent to the Function constructor. This is also close to how the bundlers nowadays work. They usually wrap our modules into closures and have similar code for resolving imports.

Producing markup as a result

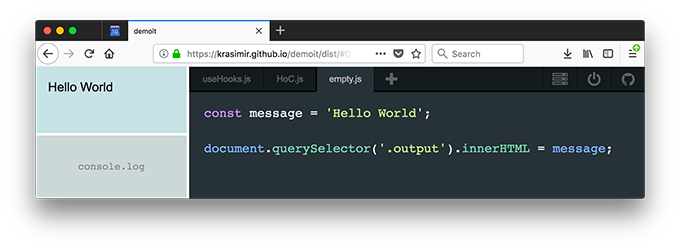

There is no much of a work here. I just had to provide a DOM element and let the developer knows about it. In the case of Demoit I placed a <div> with class "output".

Look at the following screenshot. It illustrates how we can target the top-left panel:

The code that comes from CodeMirror is executed in the context of the same page where the app runs. So, the code has access to the same DOM tree.

There was one problem that I had to solve though. It was about cleaning the <div> before running the code again. This was necessary because there may be some elements from the previous run. A simple element.innerHTML = '' didn't work properly with React so I ended up using the following:

async function teardown() {

const output = el('.output');

if (typeof ReactDOM !== 'undefined') {

ReactDOM.unmountComponentAtNode(output);

}

output.innerHTML = '';

}

If the code uses ReactDOM package we make the assumption that the React app is rendered in the exact that <div> and we unmount it. If we don't do that we'll get a runtime error because we flushed the DOM elements that React is using. unmountComponentAtNode is pretty resilient and does not care if there is React in the passed element or not. It just does its job if it can.

Catching the logs

While we code we very often use console.log. I needed to catch those calls and show them on the lower left panel. I picked a little bit hacky solution - overwriting the console methods:

const add = something => {

// ... add a new element to the panel

}

const originalError = console.error;

const originalLog = console.log;

const originalWarning = console.warn;

const originalInfo = console.info;

const originalClear = console.clear;

console.error = function (error) {

add(error.toString() + error.stack);

originalError.apply(console, arguments);

};

console.log = function (...args) {

args.forEach(add);

originalLog.apply(console, args);

};

console.warn = function (...args) {

args.forEach(add);

originalWarning.apply(console, args);

};

console.info = function (...args) {

args.forEach(add);

originalInfo.apply(console, args);

};

console.clear = function (...args) {

element.innerHTML = '';

originalClear.apply(console, args);

};

Notice that I kept the usual behavior so I didn't break the normal work of the console object. I also overwrote .error, .warn, .info and .clear so I provide a better developer experience. If everything is listed in the panel the developer doesn't have to use the browser's dev tools.

All together

There is also some glue code, some code for splitting the screen, some code that deals with the navigation and local storage. The bits above were the most interesting and tricky ones and probably the ones that you have to pay attention to. If you want to see the full source code of the playground go to github.com/krasimir/demoit. You can try a live demo here.